Highest Level of World’s Most Toxic Chemicals Found in African Free-Range Eggs: European E-Waste Dumping a Contributor

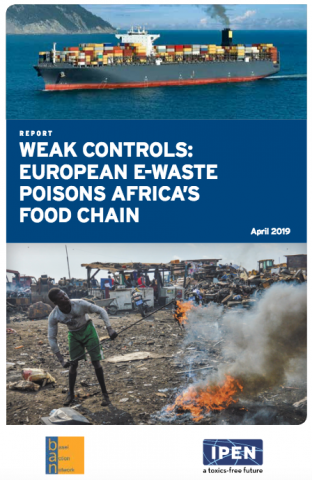

(Göteborg, Sweden): New research from IPEN and Basel Action Network (BAN) reveals dire human exposures and food chain contamination from highly toxic plastics in waste in Ghana that includes toxic e-waste shipped from Europe. Researchers have found the highest levels of brominated and chlorinated dioxins— some of the most hazardous chemicals on Earth— ever measured in free-range chicken eggs in Agbogbloshie, Ghana. The contamination results primarily from the breaking apart of discarded electronics (e-waste) and burning plastics to recover metals. Plastics from vehicle upholstery are also burned on the site and contribute to the contamination.

Researchers analyzed the eggs of free-range chickens that forage in the Agbogbloshie slum, home to an estimated 80,000 people who subsist primarily by retrieving and selling copper cable and other metals from e-waste. The process of smashing and burning the plastic casing and cables, to extract the metals, releases dangerous chemicals found within the plastics, such as brominated flame retardants, and creates highly toxic by-product chemicals like brominated and chlorinated dioxins and furans. The sampling of eggs revealed alarmingly high levels of some of the most hazardous and banned chemicals in the world, including dioxins, brominated dioxins, PCBs, PBDE and SCCPs.

Researchers from BAN have tracked shipments of used electronic devices from Europe to Ghana. The 2018 BAN report Holes in the Circular Economy: WEEE leakage from Europe revealed how e-waste from homes and businesses in Europe were fitted with electronic trackers and traced to developing countries. In Africa, the European e-waste was illegally dumped in Ghana along with locations in Nigeria and Tanzania.

Key findings from the Ghana egg analysis:

- An adult eating just one egg from a free-range chicken foraging in the Agbogbloshie scrap yard and slum would exceed the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) tolerable daily intake (TDI) for chlorinated dioxins by 220-fold.

- The typical daily egg consumption per person in Ghana is less than one egg a day, but even eating 2.5 grams of an egg per day would exceed the EFSA TDI by more than 15-times.

- PCBs (banned in the US in 1979, the UK in 1981, the EU in 1987) in these eggs were four-fold higher than the EU standard and 171-fold more elevated than the standard for dioxins and dioxin-like PCBs.

- The eggs also contained very high levels of PBDE flame retardants and the metal cutting and PVC processing chemical SCCP, as well as relatively high levels of other POPs, such as pentachlorobenzene and hexachlorobenzene.

The report references data from a larger egg sampling study, the newly released IPEN, ARNIKA, and CREPD study Persistent Organic Pollutants in Eggs: Report for Africa, which reveals how weak controls in international treaties allow developed countries to export e-waste to developing countries, leading to dangerous food chain contamination. The grim evidence, say researchers, calls for immediate action to strengthen international laws restricting hazardous chemicals in waste and to list brominated dioxins in the Stockholm and Basel Conventions at the upcoming Conference of the Parties.

The export of e-waste and the toxic chemicals they contain could be prevented by agreement on tougher hazardous waste limits in the Stockholm Convention, known as Low POPs Content Levels (LPCL). POPs waste, as defined by the LPCL, cannot be exported to countries that do not have the advanced infrastructure to destroy it. The adoption of the strict new levels proposed by IPEN would effectively end this toxic trade. Researchers also call for the listing of brominated dioxins in the Stockholm Convention.

"Europe needs to contend with its toxic e-waste rather than routing it to developing countries, such as Ghana, where hazardous chemicals contaminate populations (especially the vulnerable) and the environment, as a result of mishandling and existing indiscriminate disposal practices. African countries should not be used as e-waste dumping grounds anymore as we do not have technological capacity to deal with waste containing high levels of persistent organic pollutants," said Sam Adu-Kumi of the Ghana Environmental Protection Agency and former President of the Conference of the Parties to the Stockholm Convention.

“Dioxins are extremely toxic in very small amounts; there is a concern when these substances are identified in even tenths of pictograms,” said Jindrich Petrlik, lead author of the report, Director of Arnika’s Toxics and Waste Programme and Co-Chair of IPEN’s Dioxin, PCBs, and Waste Working Group. “However, our sampling revealed levels measured in very high quantities, indicating vast amounts of these unregulated, highly toxic chemicals are reaching Africa in e-waste and entering the food chain. This is an environmental health catastrophe that can be addressed. The Stockholm and Basel Conventions should more strictly regulate dangerous chemicals in plastics and create stricter limits on brominated flame retardants and dioxins in waste.”

As the Basel Action Network’s Jim Puckett – a toxic trade activist for the last 30 years – put it: “If somebody forced another human being to inhale or ingest poison, it would be considered attempted murder at the very least. Yet every day, electronics manufacturers allow chemical inputs into their electronic products that kill. And every day these same toxic products at end of life are exported to developing countries where they have the least capacity to prevent this outcome. We have got to consider both of these activities as the crimes they are.”

###

Editors and reporters please contact Laura Vyda (LauraVyda@IPEN.org +1 510-387-1739) to arrange interviews with the authors and request additional information.

Editors are welcome to use the photographs in the report with photo credit: Martin Holznick, Arnika.